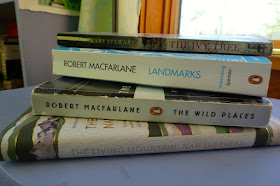

This month's reading selections reflect a small obsession with British nature writer Robert Macfarlane. It started with me running across a video of Macfarlane giving a talk. That reminded me how much I'd enjoyed reading Mountains of the Mind a few years ago, that I had checked Landmarks out from the library when it first came out but quickly decided I wanted my own copy and returned it unread (and never got around to buying it), and that I had a copy of The Wild Places, which a friend had given me and which I'd been keeping in my car for emergencies of the "a long wait and nothing to read" type. Fortunately or unfortunately, I hadn't had a lot of that type of emergency and had only gotten partway through the book. So I brought it inside and added it to the nightstand and bought myself a copy of Landmarks.

This month's reading selections reflect a small obsession with British nature writer Robert Macfarlane. It started with me running across a video of Macfarlane giving a talk. That reminded me how much I'd enjoyed reading Mountains of the Mind a few years ago, that I had checked Landmarks out from the library when it first came out but quickly decided I wanted my own copy and returned it unread (and never got around to buying it), and that I had a copy of The Wild Places, which a friend had given me and which I'd been keeping in my car for emergencies of the "a long wait and nothing to read" type. Fortunately or unfortunately, I hadn't had a lot of that type of emergency and had only gotten partway through the book. So I brought it inside and added it to the nightstand and bought myself a copy of Landmarks.The Wild Places is an account of Macfarlane's quest to explore the last remaining bits of wilderness in the Britain, and along the way redefining what "wild" means in the context of islands that have been inhabited by and transformed by humans for thousands of years. Landmarks is a lovely meditation on a number of nature writers, most of them British, although John Muir is included (perhaps, since he was born in Scotland, he counts as British), and all of them, I gather, having had some significant impact on Macfarlane. Interspersed with the stories of the writers are collections of words from various languages, dialects, and regions of the British Isles for natural features and phenomena, with the idea that losing the language of nature goes hand-in-hand with losing nature itself, and inversely, reclaiming the words is a step toward reclaiming the landscape.

While looking for Landmarks in a little bookstore one day, I came across a slim book with green and purple mountains edged in gilt on the cover. Macfarlane's name was on the cover as well, his introduction to the book coming from his chapter in Landmarks. The book itself, The Living Mountain, was written by Nan Shepherd in the 1940s, and is a life history of the Cairngorm Mountains in Scotland, told by a frequent visitor to, a careful observer of, and an intimate acquaintance of those plateaus and peaks.

One last Macfarlane book doesn't live on my nightstand, because it's far too big. Besides, I hope that in its home on the coffee table, it might inspire others to open its pages and read a spell. Also, it looks nice next to my current knitting project. The Lost Words is a collection of poems—a spell book, in Macfarlane's words—for conjuring up the words for wild things, plants and animals, that were removed from the Oxford Children's Dictionary. Macfarlane's poem-spells are acrostics, but not those torturous dry things our children are forced to create for Mother's Day cards. Rather they're living, breathing word worlds that really do conjure the words and the world to life. Listen to artist Jackie Morris read "Otter" while she paints an image of that creature.

Finally, another book by a British writer who pays close attention to the landscape, but through fiction. My mom sent The Ivy Tree, a 1961 suspense novel by Mary Stewart, to me, with a note that said "this is why I get so impatient with modern authors." They just can't spin a tale and use beautiful language to do it the way Stewart did. As I read the book, I was struck by how much detail of the plants, the animals, the clouds, the whole natural world came into the narrative. Even as she was running for her life, the heroine took the time to mention the species of the trees she dodged. In fact, at the risk of spoiling a nearly 60-year-old book, it's this attention to detail that helps clue the reader in as to the mystery. It also sets the mood. I marked several pages as I read. Here are just a few:

Finally, another book by a British writer who pays close attention to the landscape, but through fiction. My mom sent The Ivy Tree, a 1961 suspense novel by Mary Stewart, to me, with a note that said "this is why I get so impatient with modern authors." They just can't spin a tale and use beautiful language to do it the way Stewart did. As I read the book, I was struck by how much detail of the plants, the animals, the clouds, the whole natural world came into the narrative. Even as she was running for her life, the heroine took the time to mention the species of the trees she dodged. In fact, at the risk of spoiling a nearly 60-year-old book, it's this attention to detail that helps clue the reader in as to the mystery. It also sets the mood. I marked several pages as I read. Here are just a few:The light was fading rapidly. The long flushed clouds of sunset had darkened and grown cool. Below them the sky lay still and clear, for a few moments rinsed to a pale eggshell green, fragile as blown glass.

Presently the timber thinned again, and the path shook itself free of the engulfing rhododendrons, to skirt a knoll where an enormous cedar climbed, layer upon layer, into the night sky. I came abruptly out of the cedar's shadow into a great open space of moonlight, and there at the other side of it, backed against the far wall of trees, was the house.

Rowan was coming…. His nostrils were flared, and their soft edges flickered as he tested the air towards me. The long grass swished under his hoofs, scattering the dew in bright, splashing showers. The buttercup petals were falling, and his hoofs and fetlocks were flecked gold with them, plastered there by the dew.While it's true that I had a grad school mentor who probably would have called this "purple prose," I love this kind of writing (and I don't much care for him). I've read so many books where not a tree, not a leaf, not a blade of grass, not a cloud is mentioned in 200-300 pages, and they're so sterile, so detached from all that's living and sustaining, and just so blah, I'll take purple prose any day.

I'm unfamiliar with Macfarlane, but between you and this On Being interview, I must go seek him out. Thank you. Here's a link to the podcast (just in case!): https://onbeing.org/programs/robert-macfarlane-the-hidden-human-depths-of-the-underland/

ReplyDeleteI think you'll like him a lot. You're teh second person who's told me about that podcast—I need to take a long drive so I can listen to it!

Delete